This article by Stephen Gilburt was published by the Enfield Society in newsletter 196, Winter 2014.

Following the extension of the Great Northern Railway, via stations at Palmers Green, Winchmore Hill (and later Grange Park) to Enfield (Chase) in 1871, there was a considerable development of private houses and shops. This was increased with the extension of the Piccadilly Line, via stations at Arnos Grove, Southgate and Oakwood, to Cockfosters in 1933. Southgate planning authority wanted to ensure that there was an ordered increase in housing “to preserve health and the amenities, as more and more people are choosing Southgate for the first time, where the land offers so much that is still blissful and remote …. No cheap or nasty project [would be] allowed.” One developer advertised “A House, a Home, a Little Palace, in a convenient healthy district, purchasable by anyone with a small capital and regular income.”

Development of the Meadway estate took place following the death in 1922 of Russell Walker, the owner of Southgate House (which was to become Minchenden School). Land between Southgate High Street and The Bourne was sold to J. Edmondson and Son (later Messrs Edmondsons Ltd.) builders, who had their head office in Winchmore Hill. They had previously built high quality middle-class houses and shops in Muswell Hill and Winchmore Hill, from 1895 onwards.

Most of the roads on the Meadway estate were constructed in 1923 and 1924, before the houses were built, although the southern part of Greenway and Norman Way date from 1933.

By 1925 14 houses had been occupied in Ridgeway and 2 houses on the south side of Meadway. By 1927 26 houses had been occupied in Ridgeway and 34 Southgate houses in Meadway. Development was largely completed by 1929, although Parkway was not finished until 1932. The varied superior “Tudorbethan” style detached and semi-detached houses were built of red brick with either pebbledash or cement render and half-timbered features and gables, some of which had rusticated weatherboarding. The rustic effect was enhanced with front garden walls made from the linings of brick kilns and blast furnaces. Some of the garden walls have since been rebuilt in brick or stone. One critic in the inter-war period considered that “the popular love for the Tudor, whether bogus or genuine, [was a sign of] a wish to escape … insecure and frightening times”.

The informal rural layout of the estate was increased by bushes and trees on the verges, greens at road junctions, allotment gardens, tennis courts and the adjoining Minchenden School playing field (which is now another housing estate). A crescent of red brick and terracotta shops was constructed facing the High Street at the entrance to the Meadway estate.

In the late 1990s the character of the estate was threatened by a proposal to demolish one house and redevelop the tennis courts with new housing. In 2008 an area comprising Meadway, Bourne Avenue, Parkway, Ridgeway and parts of Greenway and The Bourne was made a conservation area to help protect the buildings and other structures such as garden walls from demolition and the use of inappropriate modern materials and inappropriate extensions. (See TES News no. 172.) Later plainer and cheaper houses at the southern end of Greenway, completed by 1936, and Norman Way, completed by 1938, were not included in the Meadway conservation area.

Buses 121, 298, 299 and W6 pass along the High Street and bus W9 passes along The Bourne. The nearest station is at Southgate, on the Piccadilly underground line.

For more information on north London suburban private houses in the 1920s and 1930s, and the way of life of their inhabitants, see Little palaces, house and home in the inter-war suburb by Mark Pinney, Phillippa Mapes, Sue Andrew and Malcolm Barres-Baker, published by Middlesex University Press in 2003. It has chapters on architecture, decoration, household management, leisure and transport. Information on suburbia can also be found in Suburban style: the British home 1840-1960 by Helena Barrett and John Phillips, published by Macdonald in 1987; Semi-detached London: suburban development, life and transport 1900-39 by A. A. Jackson, published by Allen and Unwin in 1973; London’s underground suburbs by Dennis Edwards and Ron Pigram, published by Baton Transport in 1986; Dunroamin: the suburban semi and its enemies by Paul Oliver, Ian Davis and Ian Bentley, published by Barrie and Jenkins in 1981; The 1930s home by G. Stevenson, published by Shire in 2000; and Something in linoleum by P. Vaughan, published by Sinclair-Stevenson in 1994. A view of inter-war London suburban family life can be seen in the 1944 film This happy breed.

The black and white photographs were provided by Enfield Local Studies Centre and Archive, which also has details of the case prepared for the then proposed Meadway conservation area.

Illustrations 1,2: Houses on the Meadway estate varied in size, design and layout, but many had a garage, fuel store, outside toilet and large back garden. Generally a ground floor vestibule entrance with hanging cupboard led to the entrance hall, sitting room, dining room (often with beamed ceiling and panelled walls) and kitchen. In some houses the sitting room and dining room were linked by glazed double doors. On the first floor there were up to four bedrooms, the largest of which often had its own hand basin with hot and cold water. The black and white half-tiled bathroom had a porcelain enamelled bath, a hand basin and an airing cupboard containing a hot water tank. There was a separate half-tiled toilet with a high- level cistern. The residents were proud of their new facilities and one claimed “We Southgate people in our new houses are a pretty clean and gentlemanly lot. We don’t boast about our baths and bathrooms, but the fact remains we take our ablutions seriously”.

Illustration 3: This room in the 1928 Meadway show house room had a tiled fireplace with a pointed gothic-style arch, an oak mantel shelf and a plate shelf high on the walls. There was a maid call button to the right of the fireplace and an electricity point in the skirting board. The furniture in the show house, including these studded leather-covered chairs, was supplied by Henry Haysom, a local Palmers Green store.

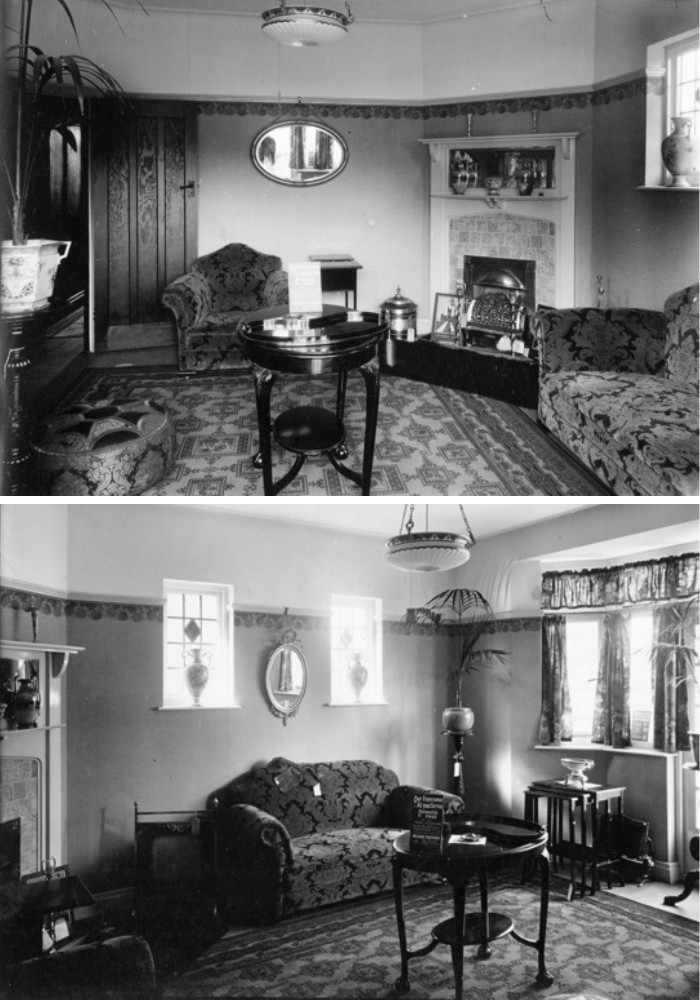

Illustration 4, 5: The sitting room/lounge where visitors would be received had a fireplace with a tiled surround and a light-coloured wooden mantelpiece, a hearth rug and a carpet. A glazed door led to the back garden. The room was furnished with a fire screen, an upholstered settee and armchairs, a pouffe, a round occasional table, a nest of three tables, a needlework box, mirrors, potted plants on stands and various ornamental vases.

Illustration 6, 7: The white half-tiled kitchen was equipped with a white glazed butler’s sink with hot and cold water, a food trolley, a cupboard, a dresser with a glass-fronted cupboard for crockery, a ventilated larder, a washing tub, an enamelled domestic boiler, a selection of pots and pans and various electrical appliances. As purchasers of the houses would have a choice, this show house displayed both a gas and an electric cooker. The cook would prepare food on the table which could also be used for servants’ meals. The display panel above the kitchen door would indicate in which room the housemaid or cook was required. Some families without live-in staff would employ a “daily” or “treasure” from the nearby working-class areas to help with the housework. However with the availability of labour-saving devices such as electric irons and vacuum cleaners, washing tubs with mangles, hot water boilers, and gas and electric fires, middle-class households in the inter-war period were increasingly servant-free.