This article by Stephen Gilburt appeared in Enfield Society News issue 210, Summer 2018.

In 2018 Enfield Market celebrates the 400th anniversary of a Royal Charter being granted by James I. Special events will include a Charter Fayre on 20th May, the market beach in July and the opening of the Old Vestry House for Open House London on 22nd and 23rd September, as well as various musical and artistic events. The first Royal Charter was granted by Edward I on 8th April 1303 to Humphrey de Bohun, his wife Elizabeth and their heirs, to hold a market every Monday at their Manor of Enfield. They were also given approval to hold two three-day fairs each year.

No regular market seems to have been established for over 100 years, probably because of harvest failures, disease and famine. However by 1419 stalls for butchers had been set up and by 1470 there was a bakehouse next to St Andrew’s church. In the late 16th century there was a Sunday meat market, which the minister (curate) of St Andrew’s, Leonard Thickpenny, incited by his vicar, Leonard Chambers, tried to stop in 1585 by attacking the butcher and throwing his meat to the ground. On 17th April 1618 a Royal Charter was granted to Olive Kidderminster Esq., six others and their heirs, to hold a market each week onSaturday. A market house and shambles (stalls for selling meat) were to be erected and the income from the market was to be used forthe relief of the poor of the parish. The present enlarged market place was created in 1632 and by 1648 there were 21 stalls and 90 trestles for the market traders. A market cross and pump were added, together with a building for the scales and weights to ensure fair trading.

In 1669 the landlord of the King’s Head inn paid £25 a year for the lease of the market. There were 24 stalls for butchers and 6 shops where Santander Bank is now. Occupants of workshops in the market place included a glazier, a horse-collar maker, a tailor and a shoemaker, who also had livestock in a nearby yard.

Picture courtesy Enfield Studies & Archive

Illustration 1. The market continued to flourish until the 1760s, but an attempt to halt its decline in 1778 failed. By then the market was only open for about one hour on Saturday. This 1793 print shows a milestone indicating 9 miles to London, a whipping post and double stocks, a pump from which women are drawing water and the 8-sided 1632 market house with timber columns, from which washing is hanging out to dry. The market house was demolished in 1810. St Andrew’s parish church was mainly built in the 14th, 15th and early 16th centuries. The muniment room over the south porch was demolished when the south aisle was rebuilt in 1824. Out of sight behind the mid-17th century King’s Head inn were the 14th century Prounces House, the 17th century Assembly Rooms and Enfield Grammar School, built in the 1590s.

Picture courtesy Enfield Studies & Archive

Illutration 2. In the early 19th century, Mr Glover, landlord of the King’s Head, ran an omnibus three times a day from outside the inn to Bishopsgate in the City of London. The fare was 2s 6d (121⁄2p) and the journey took 11⁄2 hours. By 1855 this service had ceased, following the opening of a branch railway line from the Lea Valley line at Angel Road, Edmonton to Enfield Town in 1849.

Illustration 3. After 1800 there was no regular market in Enfield until about 1870. This 1827 view of the market place shows John Hall’s 1826 market cross which was constructed as part of an unsuccessful attempt to revive the market. On the right is the 17th century Greyhound inn with its Dutch gables, which overlooked Enfield Green. After 1860 the inn was used as local government offices and a court house. Later it contained a photographer’s studio and the office of Enfield Building Society. The two cottages to the right of the Greyhound were replaced in 1829 by the beadle’s office with two lock-up cells. This Old Vestry House, which served as Enfield’s first police station, is now occupied by the Old Enfield Charitable Trust. Charles Lamb is best known as an essayist and the co-author, with his sister Mary, of “Tales from Shakespeare”. After he retired from the City of London, they lived in Chase Side, Enfield, between 1827 and 1833. However he missed the sounds, entertainment and shops of London. In 1830 he advised Mary Shelley (the author of Frankenstein) “don’t run to a country village which has been a market town but is no longer (where) clowns stand about what was the market place and spit minutely to relieve ennui (boredom)”.

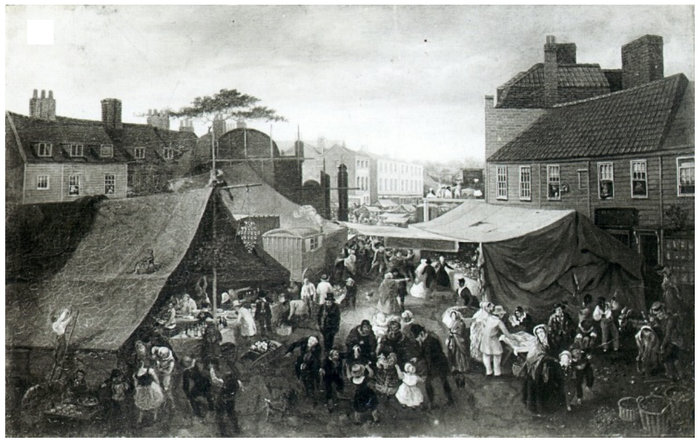

Illustration 4. After 1613 an annual fair was held behind the King’s Head for three days around St Andrew’s Day, 30th November. Cheese was at one time a speciality.

When George Forster painted this view of the fair in 1848, it was being held on Enfield Green (now The Town) for three days in late September. There were stalls selling oysters, mussels, sandwiches, gingerbread and toys. Entertainment included skittles, nut shooting, a wheel of fortune, a steam powered roundabout and swings. However, following protests, when two men were arrested for “singing and selling songs of an indecent tendency”, the fair was suppressed in 1869.

After the arrival of direct railway lines from central London to Enfield Chase in 1871 and Enfield Town in 1872, there was a rapid rise in the population of Enfield. In 1879 the Observer commented that “For a long timefew stalls have been erected in the market place, but not until the last few months have they been of sufficient importance to engage the attention of the authorities”. Traders were quarrelling over pitches and crowds were gathering to watch the extraction of teeth! By the 1890s the market had become so crowded that “ordinary traffic could not get through”. According to the Observer “the market was lit by the sizzling and fitful yellow flames of the naphtha flares [and] is full of people, mothers and fathers doing their shopping and boys and girls playing and spending their ha’pennies on sweets”. There were stalls for provisions, fish, whelks, crockery, hosiery, plants, flowers, fruit and vegetables.

A drinking fountain, installed in The Town in 1885, became a place for political and religious groups to gather, occasionally both at the same time!

Picture courtesy Enfield Studies & Archive

Illustration 5. The present King’s Head of 1899 by Shoebridge and Rising has tile hung upper storeys and half-timbered gables. This 1902 picture postcard also shows a water pump and the market cross. The cross is shown after its top section had been removed, but before it was completely dismantled in 1904 and re-erected in Myddelton House rose garden. In 1910 the clock face was replaced by a smaller one near the top of the church tower, with a second face on the west side for the benefit of the staff and pupils at Enfield Grammar School.

Picture courtesy Enfield Studies & Archive

Illustration 6. This 1905 photograph, taken from the top of St Andrew’s church tower, shows on the right the Universal Penny Bazaar next to a mound of fruit. The 8-sided market house by Sidney M. Cranfield was erected in 1904 to commemorate the coronation of Edward VII in 1902. In front are the entrances to the underground public toilets, which have since been closed. In 1897 the former Greyhound inn was replaced by W. Gilbee Scott’s Flemish Renaissance style London and Provincial Bank (now Barclays Bank). The surviving part of the mainly mid-16th century Enfield Palace (Enfield Manor House) can be seen behind Pearson Brothers and other shops in Church Street. The Palace was finally demolished along with the shops in 1927 and replaced by Pearsons department store. The magnificent cedar of Lebanon, planted in 1663 by the botanist Dr Robert Uvedale, was cut down at the same time. Dr Uvedale was the headmaster of a boarding school in Enfield Palace.

Picture courtesy Enfield Studies & Archive

Illustrations 7, 8. These views show what Enfield Market looked like in 1910. The market was open to late at night when bargains were available to shoppers before it closed. After the First World War the market only flourished when cheap or scarce items were available for sale. Local shopkeepers were opposed to market trading on any day but Saturday and the police were called when fruit and flower stalls were set up during the week. From 1930 car parking was allowed. In 1932 electric lighting replaced the naphtha flares on the stalls.

Illustration 9. The market has been open on Thursday since 1974 and on Friday since 1987, when this photograph was taken, showing the stalls with striped awnings. In 2003 HM The Queen visited as part of celebrations for 700 years since the original Royal Charter. In 2011 the number of stalls was reduced, although the market still offers a wide range of items including fruit, vegetables, flowers, plants, clothes, jewellery and watches. The stalls have a variety of coloured awnings and some selling freshly cooked food are in huts, trailers or vans. The market house / bandstand has been used by various performance groups and those wishing to display their art or craftwork. Other recent attractions, for limited periods, have included funfair rides, a beach and themed foreign food stalls.

The market is managed by The Old Enfield Charitable Trust and operates on Thursday, Friday and Saturday. The market place is run by the Trust as a car park from Sunday to Wednesday. The net income from the market, car park and investments is used to make personal, educational and community grants to individuals and groups in the historic parish of Enfield. A separate charity, which operates in conjunction with The Old Enfield Charitable Trust, lets almshouses to needy local residents. For more information contact The Old Enfield Charitable Trust or see TES News nos. 178, 186 and 209, transcripts of the 1303 and 1618 charters, David Pam’s three volumes of A history of Enfield, his Enfield Town, village green to shopping precinct, and Graham Dalling’s Enfield past and The Enfield book. These may be consulted at Enfield Local Studies Centre and Archive, which also supplied illustrations 1, 2, 5, and 8.